Canada Day 2021 comes as country grapples with troubled past, present

Posted Jul 1, 2021 12:00 am.

VANCOUVER (NEWS 1130) – Canada Day is taking on a much less celebratory tone in 2021, as the country is forced to reflect on the way it has and continues to treat many of the people who live here.

Canada is in the midst of a reckoning with the way Indigenous and immigrant Canadians have been treated.

But how did we get here?

Residential schools

The residential school system in Canada began operating in the 1880s. While the majority of schools shuttered in the 1970s, the last of them didn’t close until 1996.

The system forcibly took Indigenous children from their families and put them in these schools where they were forbidden from acknowledge their heritage and culture, and were not allowed to speak their own languages.

The children were punished if rules were broken, and many of the children were also subjected physical, sexual, emotional, and psychological abuse.

The goal of the system was to “civilize” Indigenous peoples and integrate them into Canadian society.

Related articles:

-

Discovery of children’s remains at former Kamloops residential school an ‘unthinkable loss’

-

751 unmarked graves found at former residential school in Saskatchewan

-

Remains of 182 found near former residential school in B.C.

The residential school system saw 150,000 First Nations, Inuit, and Metis children taken from their families and confined in conditions that constituted cultural genocide.

To date, the Truth and Reconciliation Commission of Canada has identified the names or information of more than 4,100 children who died in the residential school system. However, the exact number remains unknown.

Though the horrific realities of the residential school system have always been part of this country’s past, Canada’s troubled history was once again put in the spotlight after the remains of hundreds of children and adults were discovered at former sites in recent weeks.

‘Legacy of colonialism, racism, and denial’

Discoveries in B.C. and Saskatchewan have sparked further searches at former residential school sites across the country, and renewed calls for Canada to take ownership of its past.

The Union of BC Indian Chiefs previously called on the federal government to take responsibility for “its legacy of colonialism, racism, and denial.”

The federal government has also been pressed by various groups to implement the Calls to Action outlined in the Truth and Reconciliation Commission report. The government has been slammed for the pace by which it has moved on enacting the recommendations.

Nunavut MP Mumilaaq Qaqqaq said in a statement in early June that Canada is only implementing two Calls to Action per year. The TRC report outlines 94 recommendations.

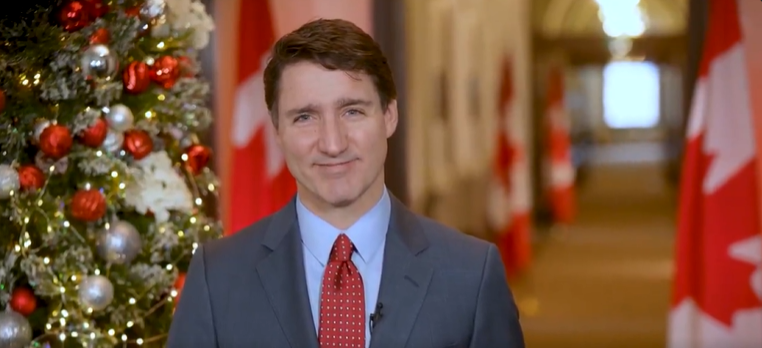

“The prime minister will be 91 by then,” she said of the time it would take to implement all of the recommendations, calling the current pace “lethargic.”

Read more:

-

Trudeau Liberals slammed over ‘lethargic’ pace on reconciliation

-

‘Pretty words, empty promises:’ Nunavut MP’s farewell highlights systemic racism, failure on reconciliation

She’s said statements and debates do not replace action.

“Who knows how many more children’s bodies would be found if we searched every single site?” the NDP MP said. “This is not a discovery but confirmation [of] Indigenous people have been talking about. Bodies buried at these schools for decades.”

Qaqqaq made headlines in recent weeks after she made an impassioned farewell speech in Parliament, following an announcement that she would not be seeking re-election.

In that speech, Qaqqaq drew attention to the “huge barriers” that prevent diverse and marginalized people from running for office, highlighting issues many people face.

“Every time I walk onto House of Commons ground, speak in these chambers, I’m reminded every step of the way — I don’t belong here,” she said in the video, which was widely shared.

“I have never felt safe or protected in my position, especially within the House of Commons, often having pep talks with myself in the elevator or taking a moment in the bathroom stall to maintain my composure,” she said, echoing a sentiment many have voiced.

The handling of cases of missing and murdered women and girls, the use of lethal force by police against Indigenous peoples, children being forcibly taken from Indigenous families, and Indigenous communities lacking access to clean drinking water are just some of examples of Canada’s complicated relationship with the original inhabitants of this land.

Immigrant Canadians face racism, discrimination

The country’s relationship with Indigenous people isn’t the only thing Canadians have been reflecting on lately.

Many Canadians have suffered through discrimination and racism throughout their lives.

Legislation targeting Chinese immigrants, the internment of Japanese Canadians, the Komagata Maru tragedy, and the various killings of Muslim Canadians are just some of the events that have tarnished this country’s history with immigrants and racialized people.

And recently, there’s been a rise in hate against certain groups once again.

The COVID-19 pandemic has amplified hate against Asian communities over the past year. In 2020 and into 2021, the number of hate crimes against Asian people rose across Canada.

Recent surveys have shown that more than half of Asian Canadians have experienced discrimination over the past year. The situation in some areas has amplified this issue, with Vancouver seeing a dramatic increase, even being named by Bloomberg as the “anti-Asian hate crime capital of North America.”

Related video: Vancouver named ‘anti-Asian hate crime capital of North America’

Canada has also been forced to reflect on how it treats BIPOC Canadians after the death of George Floyd, a Black man in the U.S. who died at the hands of police. His death sparked mass protests across the world against police brutality, especially toward Black people.

In London, Ont., a Muslim family was run down by a vehicle in early June in what police believe was an act motivated by Islamophobia.

From being told to “go back to where you came from,” to being targeted verbally and physically for their appearance, there is no shortage of stories outlining acts of racism against newcomers and other Canadians with foreign roots.

The events over the course of over a year have forced Canadians to realize that Canada is not all about cultural tolerance — that Canada has its own problems with race and acceptance.

They have shown the world and Canadians themselves that this country has more work to do when it comes to addressing racism and intolerance, with federal officials and the public alike coming to terms with this.

Cancelling Canada Day?

In light of recent events, particularly the discovery of Indigenous remains at sites of former residential schools, there have been growing calls for communities and governments to cancel Canada Day celebrations.

Several communities have responded to those calls, saying they will instead mark the national holiday with reflection and solidarity.

And many Indigenous leaders, advocates, and scholars say that’s just the start of broad efforts needed to reframe Canada Day as a reminder of the country’s dark past and present, and what it means to be Canadian.

“I think what this country is finally realizing and contemplating and thinking about is the lived reality of Indigenous Peoples,” said Terry Teegee, regional chief of the British Columbia Assembly of First Nations.

Some groups have been pushing to cancel the usual July 1 celebrations for some time, with one organizer of a Cancel Canada Day event insisting she and others who are calling for changes aren’t being divisive, but are rather “uniting under the truth.”

Related video: Is this Canada’s reckoning over Indigenous relations?

While some people want to see Canada Day events be held, many are in agreement that it’s time all Canadians learn more about this country.

“They, too, have a responsibility, because it’s education that is the first step in regards to this reconciliation,” said Howard E. Grant, executive director of the First Nations Summit. “It needs to be placed into the core curriculum of K to 12 and mandatory for at least the first two years of university for every Canadian individual to learn the history — the true history — of Canada.”

Grant joins others in calling for people to educate themselves in an effort to “make something good happen.”

“Many, as I said, won’t celebrate [Canada Day]. And I know that many will. I choose to be educated, and to revise, and to ensure that the world becomes a better place for all of us,” he said.

“I choose to continue on, but to continue on in a way that brings resolve to the aspirations of my parents and my grandparents, which is that Canada can be a better place for all of us.”