‘It took science to wake the world up’: Kamloops residential school findings released

Posted Jul 15, 2021 11:55 am.

Last Updated Jul 15, 2021 3:54 pm.

A national Indian Residential School Crisis Line is available for anyone affected by residential schools. You can call 1-866-925-4419 24 hours a day to access emotional support and services.

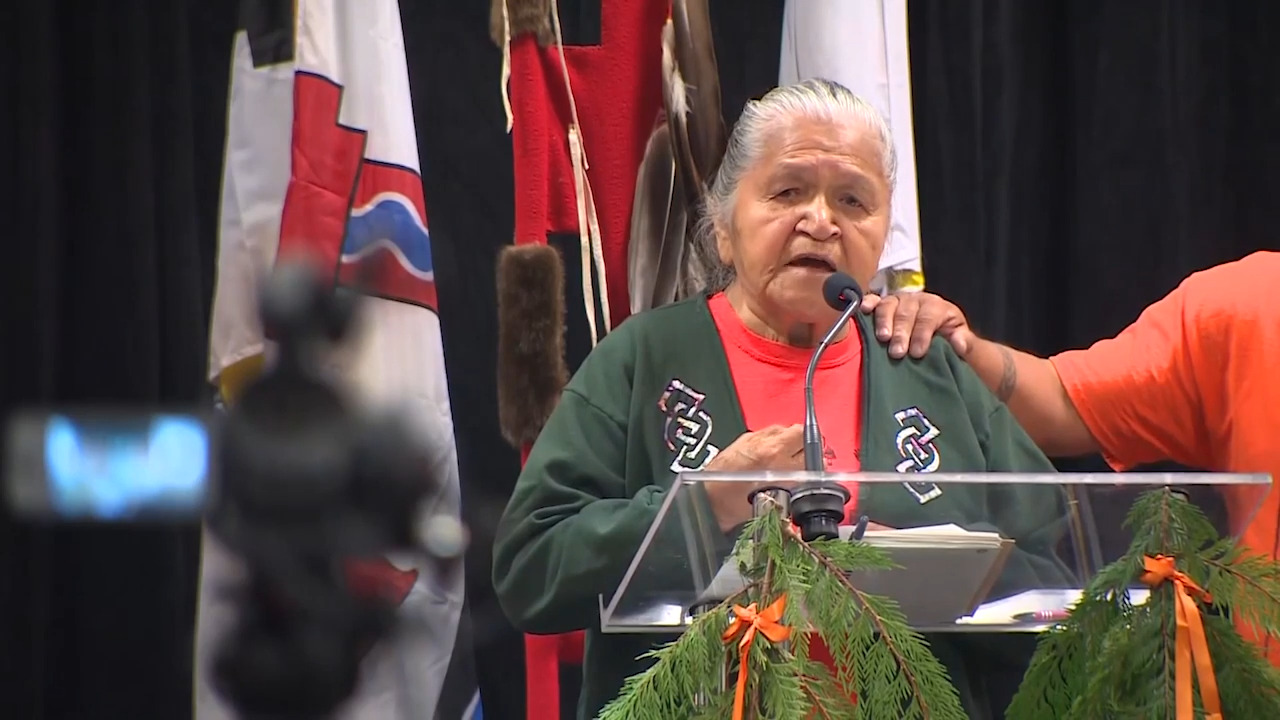

KAMLOOPS (NEWS 1130) — Residential school survivor Evelyn Camille spoke through tears Thursday as she remembered the horrors of her time spent at the Kamloops Indian Residential School. The memories were so painful, she didn’t speak about them for years, not even to her family.

“I told my youngest daughter, ‘I didn’t want you to know what happened to me.’ I was ashamed … that’s what residential schools taught me. To be ashamed of my identity,” Camille said, standing in front of First Nations leaders, science experts, and other survivors, as the Tk’emlúps te Secwépemc nation provided more details into the unmarked burial sites on the grounds of the former residential school.

She doesn’t want to call them schools.

“I didn’t learn anything there,” she said.

In tears, Camille recounted how she spent 10 years away from her family, and as a result lost her language, culture, and much more.

In May, when news spread that the Tk’emlúps te Secwépemc nation had found what was believed to be 215 children in unmarked graves, she said it was too unsettling.

Now, two months later, researchers gathered virtually and in Kamloops to address their findings through ground-penetrating radar.

Sarah Beaulieu, an anthropology and sociology instructor with the University of the Fraser Valley, says they’ve only searched about two acres of the 160-acre site. She says current estimates are about 200 bodies buried at the site of the former Kamloops Indian Residential School, but there are believed to be more.

Researchers focused their search primarily on the area around an apple orchard. She says knowledge keepers remembered being woken up in the middle of the night to dig graves for children in that area.

She says a juvenile tooth that was also found later helped narrow the search area further.

“A juvenile tooth is not an indicator of loss of life but given both discoveries, the possibility should not be discounted. As a preliminary assessment, this project sought to first ascertain the likelihood of human burials within the study area. Second, begin a preliminary assessment of the possible locations of specific burials, and finally develop steps to further this work in order to confirm the number and location of possible burials,” Beaulieu said.

Researchers were able to determine there are several burial sites, and can see the size and depth. But until the area can be excavated, it’s too soon to determine a final number of bodies buried.

Lisa Hodgetts with the Canadian Archaeological Association says this is just the beginning, and there are more than 100 more sites to search across the country. She says that will be both expensive and traumatic, and governments will need to step up to provide the resources for communities to get closure.

She echoed the sentiments of survivors, who have long said that the deaths at these sites were never kept secret.

Related Articles:

-

‘Old wounds’: Renewed interest over residential schools difficult for survivors

-

Indigenous children’s remains turned over from Army cemetery

-

‘We’ve always known’: Kuper Island residential school survivor not surprised by discovery of remains

Camille, who is a survivor, says the stories of children dying or going missing while trying to escape would be passed along, but no one had ever looked for them.

“We have tried to tell them the truth,” she said, adding she feels the study of the graves should continue, but is against disturbing the bodies. “Now that they are found we believe we have to guide them home to finish their journey.”

She says everyone needs to do their own personal way of healing and letting go.

“It took science to wake the world up,” Hodgetts said of the findings and the attention that followed.

Kukpi7 (Chief) Rosanne Casimir says it’s unfair to make survivors carry the weight of identifying the remains. She is calling on the federal government to fully release school records. She also says the prime minister has not directly reached out to her community, and is hoping dialogue between the federal government and the Tk’emlúps te Secwépemc nation can begin.

“They were children robbed of their families and their childhood. We need to now give them the dignity of the childhood they never had,” Casimir said of the next steps.

Prime Minister Justin Trudeau has expressed his condolences to Tk’emlúps te Secwépemc Nation but has not directly spoken with First Nations leaders, according to Casimir. (FILE CANADIAN PRESS)

Dr. Kisha Supernant with the Institute of Prairie Archaeology says they have released information on how other communities can and should use ground-penetrating radar (GPR) to search other residential school sites.

Also in attendance Thursday was newly elected Assembly of First Nations head RoseAnne Archibald. She says these are not discoveries, but recoveries.

“It’s time to find our children and bring them home. This agonizing exercise and grim reminder will continue until we find all our family members and bring them home, through proper ceremony,” she said, urging all Canadians to learn about the genocide of indigenous peoples.

The Kamloops Indian Residential School opened under Roman Catholic administration in 1890 and operated until 1969 under the federal government. Casimir says the Catholic Church also needs to completely open its records to help identify the remains.

Canada’s Dark History

Since the discovery in Kamloops, other First Nations have reported similar devastating findings.

The Cowessess First Nation reported 751 potential unmarked grave sites in Saskatchewan last month.

The Kuper Island School on Kuper Island near Chemainus, Vancouver Island, British Columbia opened in 1889. (Courtesy: National Centre for Truth and Reconciliation)

Earlier this week, another community in B.C. confirmed 160 undocumented and unmarked graves at the site of a former residential school. The Penelakut Tribe in B.C.’s Southern Gulf Islands did not say if ground-penetrating radar was used to examine the area where the Kuper Island Residential School once stood.

The residential school was once known as “Canada’s Alcatraz” and records indicate two sisters drowned while trying to escape the school in 1959.

The site of the former St. Joseph’s Mission Residential School will also be searched, according to the First Nation. (Courtesy: Williams Lake First Nation)

The Williams Lake First Nation will also undertake a comprehensive ground analysis of the land surrounding the former St. Joseph’s Mission Residential School. In a statement, the nation said “It is time to complete the investigation and hopefully find some form of closure on this terrible chapter of Canadian history.”