Indigenous men face worse prostate cancer outcomes: UAlberta study

Posted Jul 10, 2023 5:19 pm.

Last Updated Jul 10, 2023 7:03 pm.

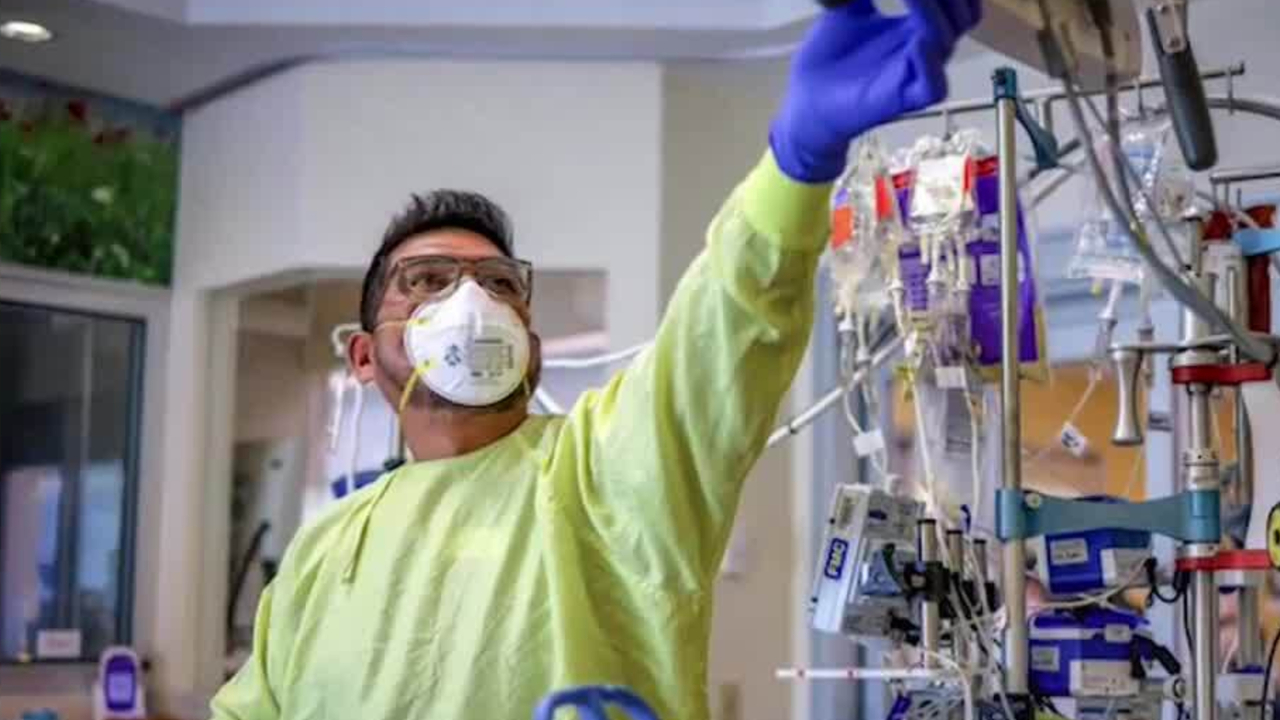

Indigenous men in Alberta are getting fewer prostate exams, leading to worse outcomes than the rest of the province, according to a study from the University of Alberta (UAlberta).

The study, published Wednesday in the journal Cancer, indicates that Indigenous men have a more aggressive disease at diagnosis and are more likely to have their cancer spread after examining the health records of 1.4 million men.

It says 32 out of 100 men in Indigenous communities received screening tests in a one-year time period, compared with 46 out of 100 men in non-Indigenous communities.

Among the more than 6,000 men with prostate cancer diagnoses, the UAlberta researchers found Indigenous men had higher screening test levels and more advanced disease.

“I wasn’t surprised by the results because they reflect what we know anecdotally about the experience of Indigenous people within the health-care system,” says study co-author Wayne Clark, executive director of UAlberta’s Wâpanachakos Indigenous Health Program, in a news release.

“We need to consider traditional practices, focus on resiliency, and shift away from deficit models when we’re looking for solutions.”

UAlberta says the study was inspired by research on the disparities of Black men’s experience in the United States, where the disparities in screening and outcomes are attributed to lower socioeconomic status and less access to healthcare resources.

Adam Kinnaird, a co-author and assistant professor in the Faculty of Medicine and Dentistry, said studies examining Black Canadians or Black British men with access to universal health care show prostate cancer outcomes are significantly lessened or eliminated altogether.

“What’s interesting is despite there being a universal health-care system here, we are seeing marked discrepancies in prostate cancer diagnoses and outcomes for Indigenous men,” Kinnaird said.

“It raises the question as to whether our public health-care system is adequately serving Indigenous Albertans or whether there is another explanation that we haven’t explored.”

Researchers to follow-up, continue research with Indigenous communities

The UAlberta researchers say they have follow-up studies planned to determine the reasons behind the disparities.

Kinnaird says they will also follow up with the men who were diagnosed with cancer for a longer period to figure out their “overall and cancer-specific mortality rates.”

UAlberta says they will work with Alberta’s Tomorrow Project, which has been gathering data on cancer in Alberta since 2000. The reason is to learn about Indigenous men living in urban areas with different lifestyles and experiences than those in rural areas.

“We know that in Ashkenazi Jewish men, as well as in men of Caribbean descent, the rates of mutations for things like BRCA1 and BRCA2 are much higher than in other men, and these are mutations that predispose to higher rates of prostate cancer, more aggressive prostate cancers and worse outcomes from prostate cancer,” Kinnaird said. “It is possible that Indigenous men also harbour some mutations that have not yet been recognized.”

He also says the researchers will team up with Indigenous collaborators and Indigenous elders to ensure the subsequent studies are “keeping up with cultural norms, wants, and beliefs of Indigenous men.”

The research team included Indigenous members, such as Elder-in-residence Patrick Lightning, Randy Little Child, the executive director of Maskwacis Health Services, and Angeline Letendre with Alberta Health Services.

In addition, the UAlberta researchers noted substandard quality of care, long wait times, and experiences of racism and discrimination were the three frequently reported barriers to accessing health care.

Meanwhile, Clark believes innovative solutions will result from bringing academic and community resources together and “creating a collaborative model that could be applied across the country.”

“We need to have a dialogue with Cree men about this to take away the stigma,” he said. “When Indigenous people are involved in program design for community-based interventions, they’re more likely to work.”

Indigenous men were also at higher risk of developing metastatic cancer than non-Indigenous men. There was no difference in mortality, though the study indicates this is likely because the follow-up period was only 40 months.

Prostate cancer is the third most common cause of death in Canadian men. According to the Canadian Cancer Society, one in eight men in Canada will develop prostate cancer, and one in 29 will die.